Pay-as-you-go (PAYGo) solar financing has electrified the homes of more than 100 million people and transformed many households that aren’t connected to the electrical grid. While evidence suggests that energy access improves women’s wellbeing and economic empowerment, it’s less clear whether PAYGo financing has any particular benefits for women. To learn more, CGAP reviewed the existing impact literature for PAYGo solar and interviewed a range of experts and industry stakeholders. While there are some indications that the PAYGo model is well suited to women’s energy and financial needs and could potentially have a positive impact on their lives, it’s clear that more rigorous research will be needed to better understand the impacts.

Photo: CGAP

PAYGo financing improves access to energy and finance for low-income households in ways that likely benefit women

Energy poverty disproportionately affects girls and women in poor households. Women spend more time and effort than men collecting and preparing wood and other household fuels, face heightened risks from indoor air pollution, and spend a larger part of their day on domestic chores. This often leaves little time for productive activities. Women are also more likely than men to be financially excluded. Despite significant progress, the gender gap in account ownership in developing economies remained about 9 percentage points between 2011 and 2017. Taken together, inadequate access to energy and finance has implications for women’s time, health, economic and social status, and it makes it harder to escape poverty.

Self-reported data from PAYGo providers and anecdotal evidence suggests that PAYGo financing models improve access to both energy and finance for poor households. While sex-disaggregated data on the impact of these models is in short supply, there are good reasons to hypothesize that there may be specific benefits for women.

The grid electrification literature clearly shows that access to energy can have transformative effects on women. These include increased participation in non-farm jobs outside their homes, increased labor productivity, greater hourly wages and improvements in child schooling outcomes like school enrollment, weekly study time and test scores.

Whether PAYGo electrification can lead to similar impacts is an open question, since it powers much smaller appliances. However, CGAP and FIBR interviews with over 130 households in Africa shows that low-income households value off-grid devices and are willing to finance them with PAYGo loans because light is useful and provides a sense of safety and comfort. Over the years, the range of PAYGo devices has expanded from solar lamps and mobile phone chargers to larger household appliances like solar home systems, cookstoves, refrigerators and solar water pumps. Evidence is emerging that these appliances can reduce women’s workloads at home, provide greater flexibility in how and when they perform domestic chores, and free up more of their time for income-generating activities.

PAYGo financing has also expanded households’ access to financial services that may prove useful to women. It is well known that formal credit is often beyond women’s reach because they lack the credit history or assets to collateralize loans. Asset-based financing models like PAYGo solar offer a way around this challenge. They enable customers to build transaction histories that financial services providers can use to underwrite loans and increase women’s access to finance. These models also offer flexible payment options that are better suited to women’s needs than traditional loans. Recent research also shows that once a device has been paid off, it can be re-collateralized for subsequent loans to meet other household needs, such as paying for children’s school fees.

More rigorous research and sex-disaggregated data is needed to better understand the impact on women

Despite the rapid growth of PAYGo financing, sex-disaggregated data and evidence for impact on women remains scarce and anecdotal. In our review of the impact literature, we found only a few studies that document the impact of these financing models on women:

-

An IGC study in Tanzania finds that access to PAYGo solar lamps increases the likelihood of women working outside the household by 5 percentage points, equivalent to an increase of 40 minutes of paid work and 24 minutes of unpaid work per day.

-

An Ashden report shows that women who have access to PAYGo solar lamps and solar home systems in Tanzania feel they have more flexibility in how they use their time for different tasks, such as domestic chores, cooking, and childcare.

-

Other reports show that PAYGo off-grid devices enable some women to start new businesses, such as charging people to watch TV or charge their phones at their homes, selling home-cooked food or making textiles.

More impact research is needed. Existing literature focuses on household-level impacts. One question that will be important to answer is how intrahousehold gender dynamics determine how devices are used and whose needs are prioritized. We know that PAYGo solar devices are often paid for by reducing women’s household budgets. Therefore, the impacts of PAYGo solar access on women may be muted, even if there are gains at the level of the household. Furthermore, since most PAYGo solar devices generate only small amounts of power, they may have only modest impacts on women’s wellbeing, which may be detected only in large sample impact studies.

In our conversations with gender experts and PAYGo providers, it became clear that, impact aside, there are questions around the extent to which women are able to access PAYGo financing in the first place.

One set of barriers has to do with the prerequisites for accessing PAYGo financing. Women are less likely than men to have the money for down payments on devices or to have the IDs required to sign contracts. Women also lag men in mobile phone ownership, the use of digital technologies and digital financial literacy, which presents a problem because PAYGo customers repay their loans digitally. Restrictive social norms around women’s ownership of assets, handling of money and control over resources create additional gender-based barriers.

Another set of barriers has to do with providers’ approach to distributing PAYGo financing. Providers generally do not treat women as a distinct customer segment or have gender-targeted business strategies. Moreover, men comprise most of their sales teams and may lack the tools or incentives to target women customers. Finally, PAYGo solar devices tend to be marketed as modern technologies that “transform lifestyles.” There is little emphasis on how they can benefit women specifically, such as saving them time with household chores or ensuring cleaner air in the home.

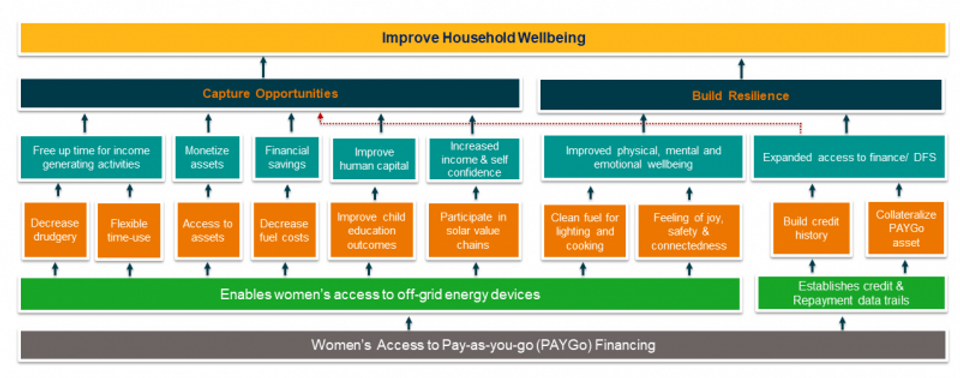

More research is needed to understand and address these barriers and questions around both access and impact. To guide such research, CGAP has developed a theory of change based on our review of the PAYGo literature and consultations with sector experts, gender specialists and women’s financial inclusion practitioners.

Theory of Change for impacts of PAYGo solar access on women's wellbeing

Image: CGAP

Researchers and donors have an important role in addressing knowledge gaps

Without more data and research on how women engage with and benefit from PAYGo, it is difficult to fully understand PAYGo's true potential for women’s empowerment. Providers should report sex-disaggregated customer data to quantity current levels of access, diagnose barriers, design solutions and facilitate research. Researchers should evaluate the PAYGo solar model’s effects on women’s wellbeing, expanding the impact evidence base and catalyzing gender-smart investments in the sector. Finally, funders can support gender-focused impact research on PAYGo solar and ensure providers have the resources to collect and analyze gender data.

This article was originally published by CGAP.