Rural women are limited by labor. They have less access than men to the labor they need to power their farms, constraining their productivity, income, and resilience and driving the gender gap in agricultural output. Financial service providers have a role to play by designing and delivering responsive solutions that help increase rural women’s access and returns to labor.

Among women and men farming similar-sized plots in similar contexts in Sub-Saharan Africa, the differences in their agricultural productivity range from 23% in Tanzania to 66% in Niger. This means that in Niger, for example, male-managed plots yield on average 66% more per hectare than female-managed plots.

Lack of labor available to rural women has important implications at both the household and national levels

At the household level, when women with agricultural livelihoods lack the labor they need, yield and quality decline, leading to lower prices for their outputs and reduced income. In Côte d'Ivoire, for example, women growing cotton could not harvest at the optimal time due to their limited access to labor. The later cotton is harvested, the harder it is to spin, and cotton bolls harvested late are sold for prices 10% lower per kilogram. In Ghana, women growing tomatoes harvested their crops over a longer time period than men, due to time constraints and lower access to hired labor, which led to significantly higher levels of post-harvest loss.

At the national level, rural women’s labor constraints also have large economic costs. In Malawi and Tanzania, for example, women’s lower access to farm labor is one of the largest drivers of the gender gap in agricultural productivity. Closing the gap in the male labor that women farmers use could yield gross gains of over $45 million in Malawi and over $100 million in Tanzania.

Women in rural and agricultural livelihoods have less access to and lower returns from labor

Labor constraints affect women in rural and agricultural livelihoods (WIRAL) in various ways: WIRAL have less access than men to both household labor and hired labor and get lower returns to the labor they do hire. Let’s look at data from Ethiopia, Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Tanzania and Uganda and then explore how financial services can play a positive role in increasing WIRAL’s access to and returns from labor.

1. WIRAL have less access to household labor

Female farmers in Malawi, Niger, southern Nigeria and Tanzania deploy fewer laborers from their households on their plots, particularly male household members. Why? One reason is that female farm managers live in households with fewer men compared to their male counterparts, possibly due to widowhood, divorce or migration. Another is that men tend to have greater control over the allocation of their household’s labor, including that of their wives and children, and often prioritize the use of family labor on their own farm plots and businesses.

This leads to starkly different patterns of labor use on men’s and women’s plots, even when comparing similar profiles of farmers. In Malawi, for example, male plot managers used 542 hours of male household labor per hectare, while female plot managers used only 407 hours: a 33% gap in favor of male plot managers.

2. WIRAL have less access to hired labor

In addition to WIRAL having less access to labor within their own household, women managing farm plots also hire less external labor compared to men farming similar-sized plots in similar contexts. The latest data from Niger, for example, indicates that female-managed plots use 16% fewer hired-labor days than male-managed plots. The fact that women farmers use less non-family, hired labor on top of limited household labor further limits their output and income.

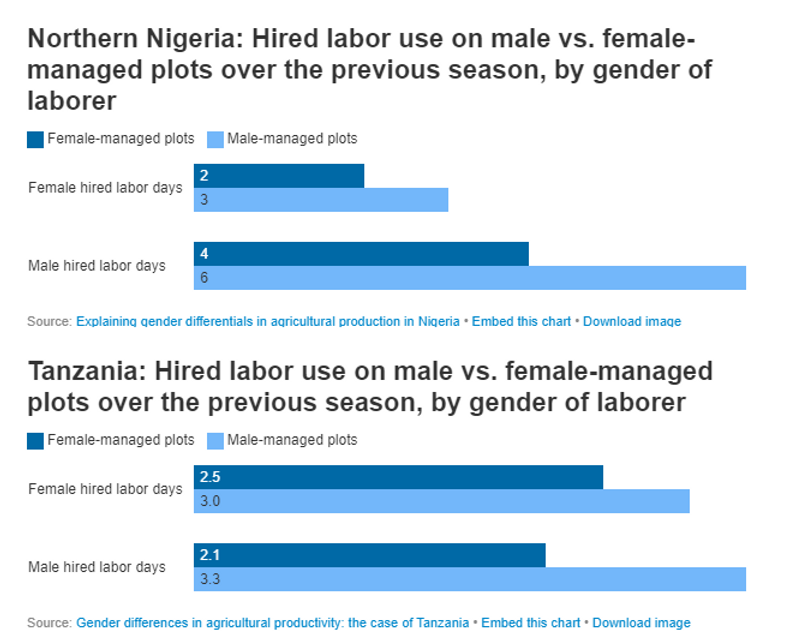

Moreover, there are clear differences in the gender composition of hired labor. As shown in the chart below, male-managed plots in Nigeria, for example, use 50% more female labor and 65% more male labor than female-managed plots — a 15 percentage-point difference. If male laborers have more physical strength or are simply able to provide more (and more focused) labor hours due to having fewer domestic responsibilities, then female farmers face a double bind: Not only are they able to hire less labor, but the labor they do hire is less productive. This leads us to lower returns from labor, our third dimension.

3. WIRAL get lower returns than men on labor

Not only do WIRAL deploy less household and hired labor than men, they also face lower returns to that labor compared to men (i.e., their agricultural yield increases by less even when they use the same amount of labor as men). In Ethiopia, Malawi, Tanzania and Uganda, for example, female farmers get lower returns from their household male farm labor than men. And in Niger and Tanzania, women farmers using external laborers get lower returns on that hired farm labor than their male counterparts.

These results underscore how improving access to labor is essential yet insufficient. To close these gender gaps in agricultural productivity, we must tackle the market failures and institutional constraints underlying these gender differences in how farmers benefit from labor.

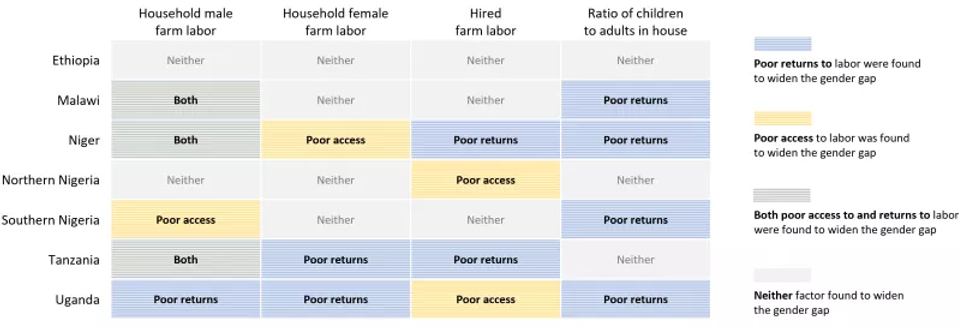

Labor’s role in widening the gender gap in agricultural productivity

Click image to enlarge. This figure shows the labor-related factors that widen the gender gap in agricultural productivity. For example, female farmers’ lower use of hired labor constrains their productivity in Uganda and northern Nigeria, while in Niger and Tanzania what matters to explain the productivity gender gap is their lower returns to hired labor.

What drives WIRAL’s limited access and returns to labor?

Constraints related to gender norms, time and financial services limit WIRAL’s access and returns to labor with variation across cultural and geographical contexts.

-

Gender norm constraints. Gender norms, a subset of social norms, are collectively held expectations and perceived rules for how individuals should behave based on their gender identity. Gender norms may make it awkward or inappropriate for women to hire, interact with or supervise men, and condition farm laborers to work harder for male managers. Norms may also restrict the size and scope of women’s networks, hampering their ability to source labor. Women’s agricultural activities may also be perceived as less meaningful than men’s, and therefore not worth more household time or money than she alone can provide.

Photo: CGAP / Stephen Ouma

-

Time constraints. Women typically have more – and more time-consuming – roles in dependent-care and household management than men. This comes out in Figure 4: the higher the proportion of children to adults in the household, the lower the returns to women’s agricultural productivity. Indeed, time-use analysis in nine African countries found that women spend an average of 15-22% of their time on household tasks (like cooking, washing clothes and fetching water and fuelwood) compared to 1-9% for men. This leaves rural women little time to engage in their own agricultural and economic activities, let alone find, hire and effectively supervise laborers. In addition, women’s responsibility for household chores and cooking meals can limit their participation in alternative ways to source labor like reciprocal labor groups. These gendered demands on women's time make their access to hired labor all the more important.

-

Cash and financial services constraints. Global Findex data in Sub-Saharan Africa shows a gender gap of 12 percentage points between women and men’s ownership of accounts with formal financial institutions. Women are also less likely to own mobile phones, particularly in rural areas; in Mozambique, the gender gap in mobile phone ownership is 16% in urban areas and 33% in rural areas – about double. Without cash on hand or access to credit, savings and other financial services, and with less access to enabling assets and technology like mobile phones, women managers are less competitive in the market for hired laborers. They cannot afford to pay the wages – at the rate or in the timeframe – that more skilled, effective laborers demand.

How might financial service providers (FSPs) play a role in increasing WIRAL access and returns to labor?

These four actions are a good start:

-

Design financial services tailored to WIRAL hiring workers. This should include short-term “labor loans” to hire workers at critical points in the growing season and wage payments to compensate them.

-

Partner with labor-matching services connecting women managing farms and businesses with laborers seeking safe, decent work. FSPs could work with these local agents, agricultural extension service providers, and other development partners to facilitate wage payments, build relationships with new customers, and then offer other financial services.

-

Offer financial services within bundled interventions that combine time-saving assets, training on climate-smart approaches, inputs, labor-matching services, access to markets, as well as credit, savings, and insurance. Work with partners to deploy these holistic solutions designed to help WIRAL increase productivity and income and build financial resilience.

-

Design interventions to address gender norms, which could include engaging husbands to take on a more equal share of domestic work, and enlisting men and community leaders as allies by using marketing and media campaigns to celebrate women as capable managers, users of financial services and decision-makers on farms and in businesses.

These innovative interventions may help close the gender gap in agricultural production and income and ensure that rural women’s livelihoods thrive. Additional research and experimentation will help identify the most effective solutions and their implications.

This article was originally published by CGAP.