The key to unlocking solutions to our most pressing social and economic problems lies hidden in plain sight: investing in African agriculture. Yet, this critical sector is underfunded and overlooked, despite holding the power to lift millions out of poverty and feed a growing global population. By the World Bank’s estimates, boosting agriculture’s output is two to four times more effective in raising incomes among the poorest compared to other sectors. It is one of the most powerful tools to end extreme poverty, boost shared prosperity, and feed a projected 10 billion people by 2050. It just needs to be harnessed and unleashed.

Nowhere is agriculture more central to poverty reduction than in Africa. The continent is home to 60% of the world’s uncultivated arable land, but low crop productivity and a lack of adequate investment leaves this opportunity untapped. More than half of sub-Saharan Africa’s workforce is employed in agriculture, and 90% of businesses in the agri-food sector are small and medium enterprises (SMEs), situating them firmly as the backbone of African food systems. Supporting and investing in these businesses is what will build and strengthen our food systems for the foreseeable future.

ACUMEN’S ANALYSIS

In light of these statistics, we conducted an analysis – similar to our recent exploration of the Productive Use of Energy sector – using the “Africa: The Big Deal” database to answer the following questions: How much capital is going into smallholder agriculture? For companies that center the smallholder farmer, how much and what type of capital are they attracting? And what can this tell us about what agribusiness SMEs need?

We first coded the database based on where companies operate in the value chain:

- Upstream business models refer to companies that are focused on helping increase or improve production.

- Midstream models focus on logistics, processing, and wholesaling.

- Downstream refers to retailing and consumption companies.

- Vertically-integrated business models incorporate features of upstream, midstream, and downstream models.

- Agribusinesses that provide purely financial services were split into their own category.

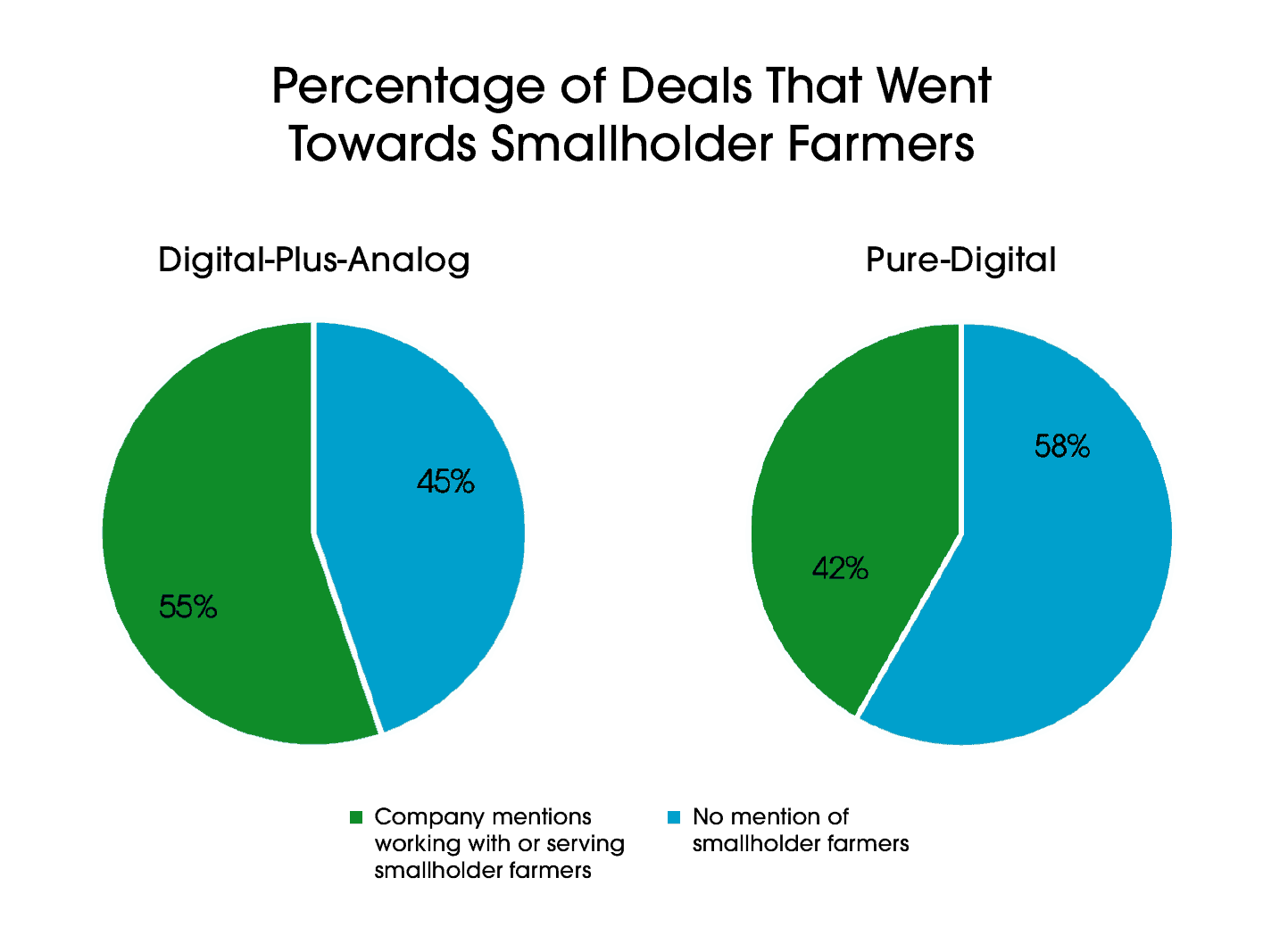

Next, we looked at whether or not they mentioned working with or serving smallholder farmers, and whether or not their solution was pure-digital (services over a phone app or website) or digital-plus-analog (at least one in-person interaction between the company and the smallholder farmer).

Our analysis makes it clear: the amount of African agriculture investment is scarce, it is becoming scarcer, and agribusinesses are not receiving nearly enough capital. Here is more on what we found.

AGRICULTURE CONTRIBUTES SIGNIFICANTLY TO LIVELIHOODS AND ECONOMIES, BUT RECEIVES LITTLE INVESTMENT IN RETURN.

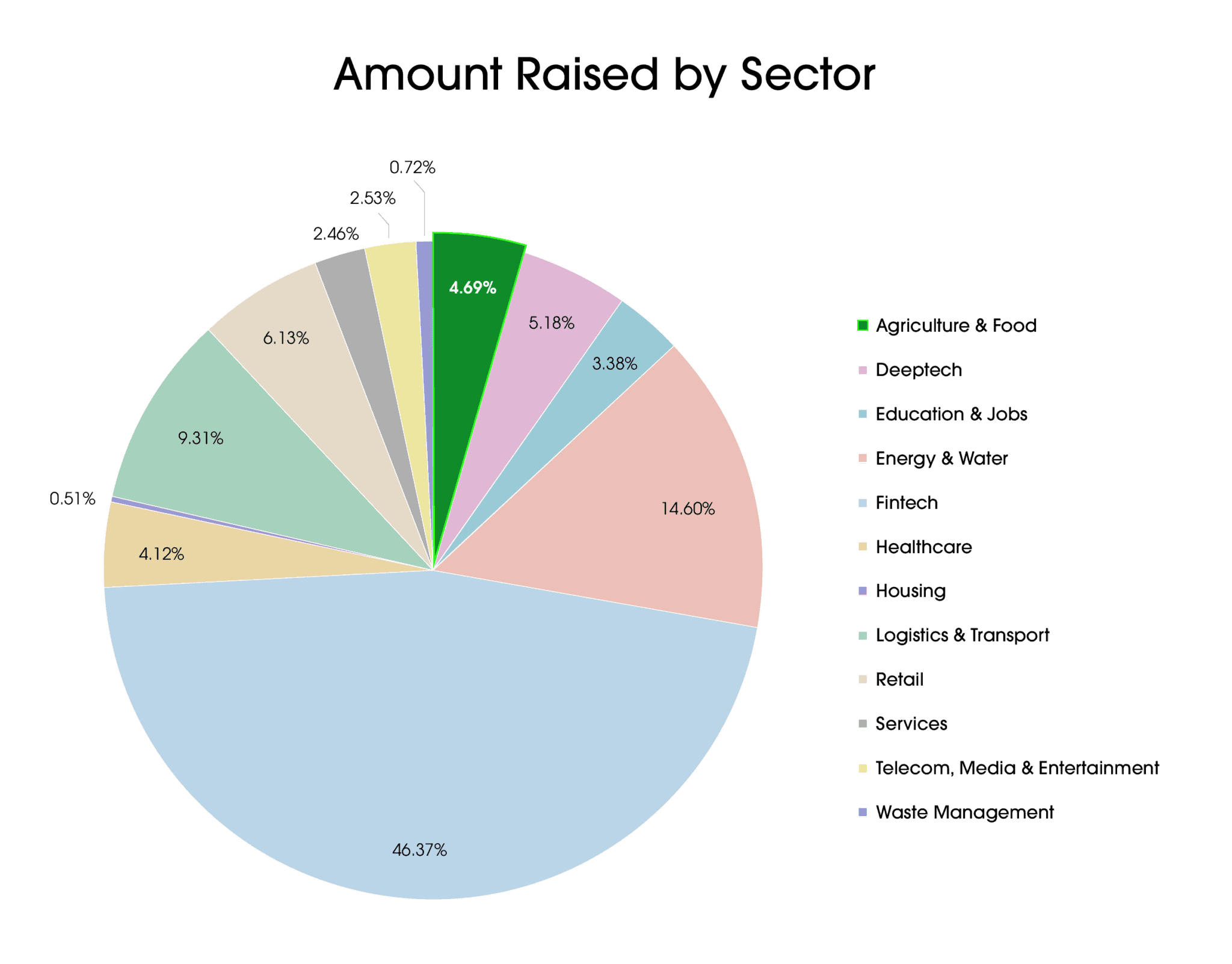

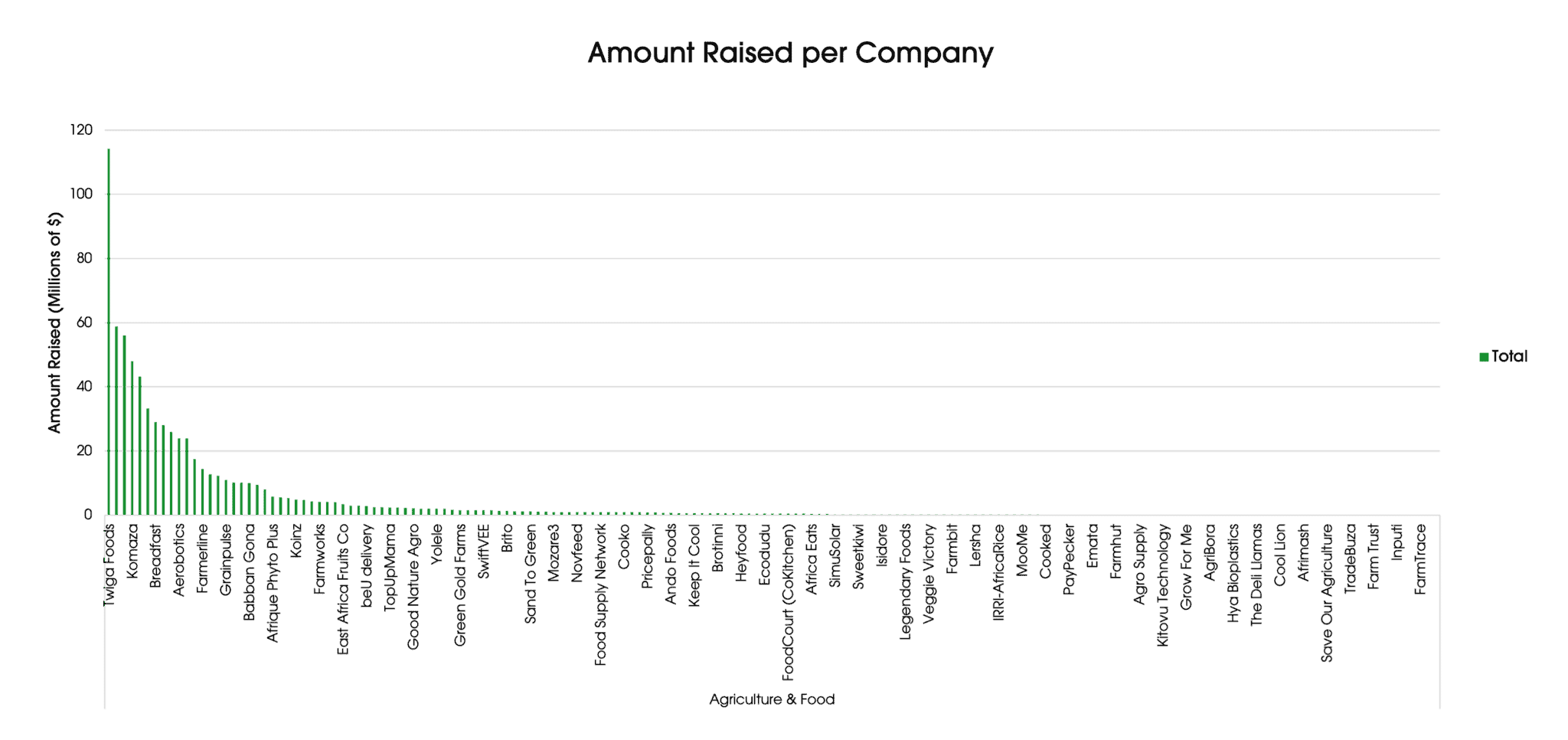

Despite agriculture’s incredible contribution to livelihoods and food production, the sector receives an underwhelming proportion of investments. In the last four years, agriculture and food received 4.69% of funding. In comparison, 46.37% of total funding went to fintech, followed by energy and water at 14.6%. The scale potential in fintech is much vaster, making it a more attractive investment. Agriculture’s highest raise (Twiga) received less than 20% of the highest fintech raise (MNT-Halan), which received $670 million. Despite agriculture’s contribution to the continent’s employment and GDP, because it is a much more challenging and less remunerative sector, with different implications for scale, it does not attract the same quantity of capital.

The GIIN has similar findings; although 61% of impact investors put some capital into agriculture, only 7% of assets under management are actually allocated towards the sector. Additionally, only 4% of climate finance went towards agrifood systems in the past year. While a majority of impact investors know that agriculture is important, the sector is not receiving the necessary capital.

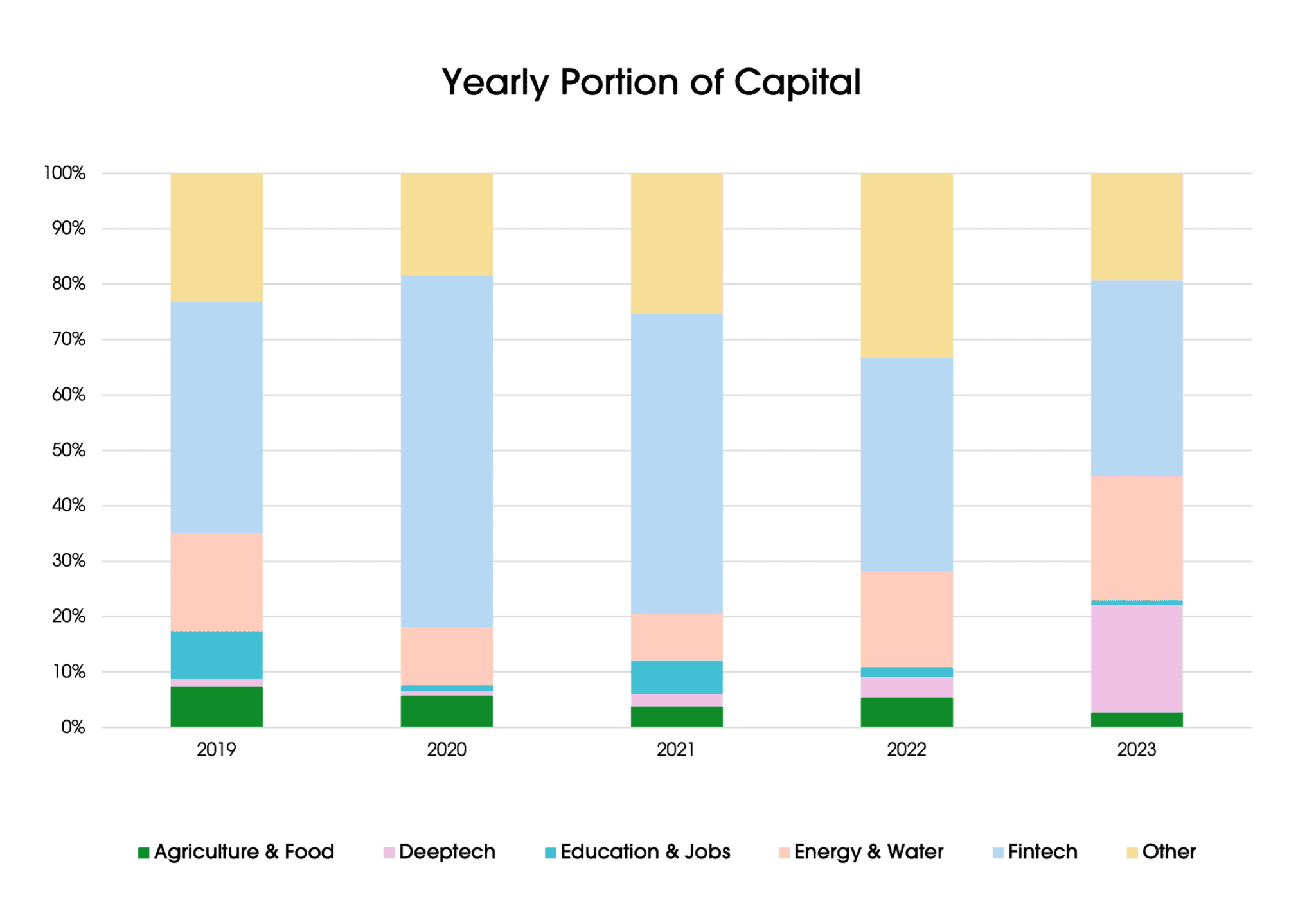

THE PORTION OF CAPITAL THAT AGRICULTURE RECEIVES HAS BEEN DECREASING.

In 2019, agriculture received over 7% of that year’s investment funding. It reached its lowest level in 2021 with less than 4% of funding, and 2023 is likely to be even lower. Admittedly, the Africa Big Deal database primarily tracks VC funding, and traditional VC is known for its short timelines and high-return expectations – two characteristics squarely opposed to the realities of agriculture. Traditional ways of investing are only applicable for a small portion of companies that have potential for dramatic scale, often through technology that rarely impacts smallholders. While VC funding can play a role, the majority of SMEs operating in sub-Saharan Africa need flexible, patient capital, and a lot more of it.

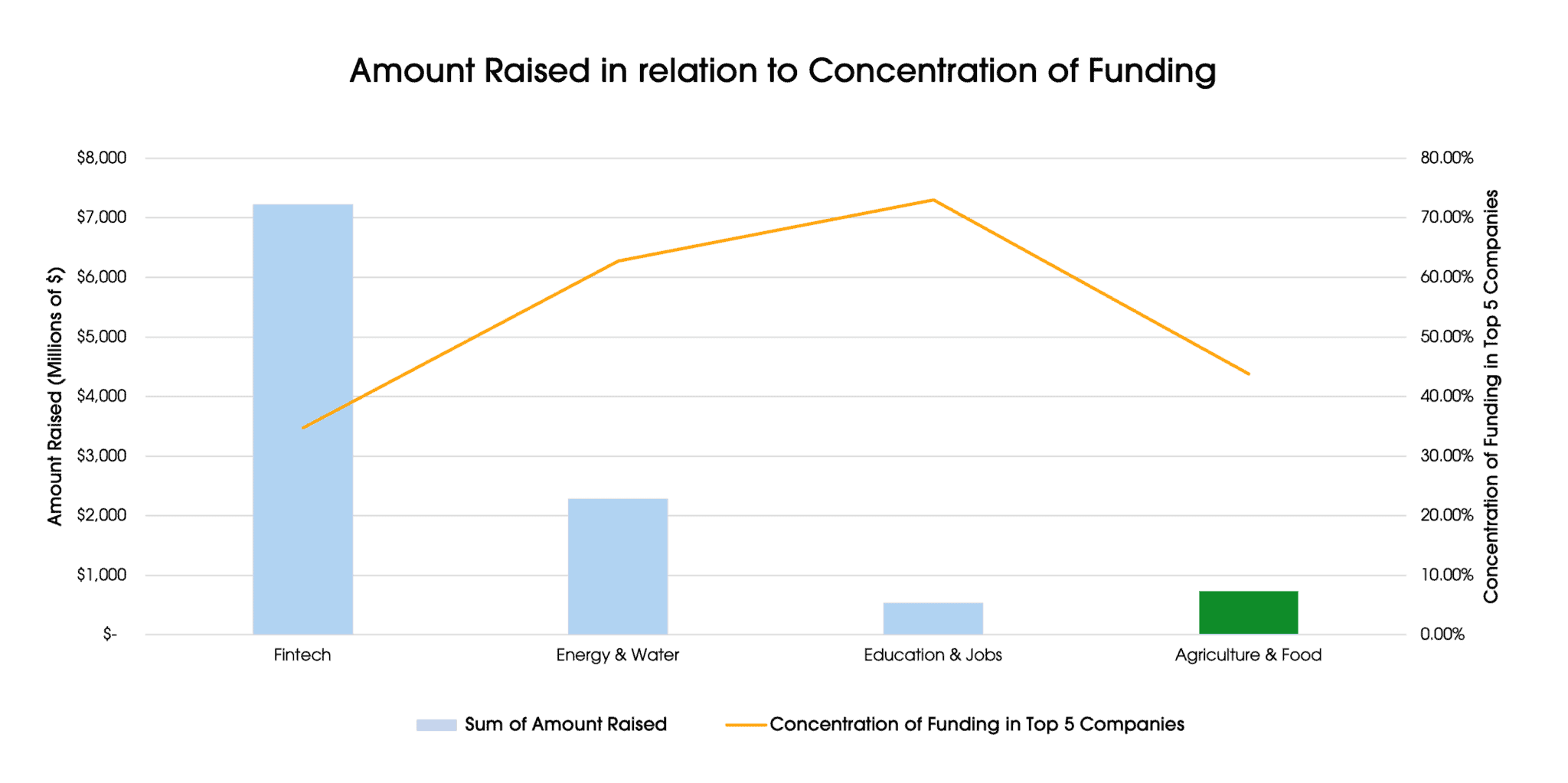

LOTS OF COMPANIES, BUT NOT ENOUGH CAPITAL.

The concentration of funding in agriculture is lower than we expected, given the amount of funding it receives. The correlation between amount raised and concentration of funding in fintech, energy, and education suggests an inverse relationship: more funding, less concentration or less funding, more concentration. Instead, we see that a lot of ag companies are raising very little capital: less funding and less concentration. Agribusinesses are not receiving enough capital, with nearly half of companies receiving less than $500,000. While that amount might be appropriate for some agribusinesses, the overall amount going into the sector is still far too meager.

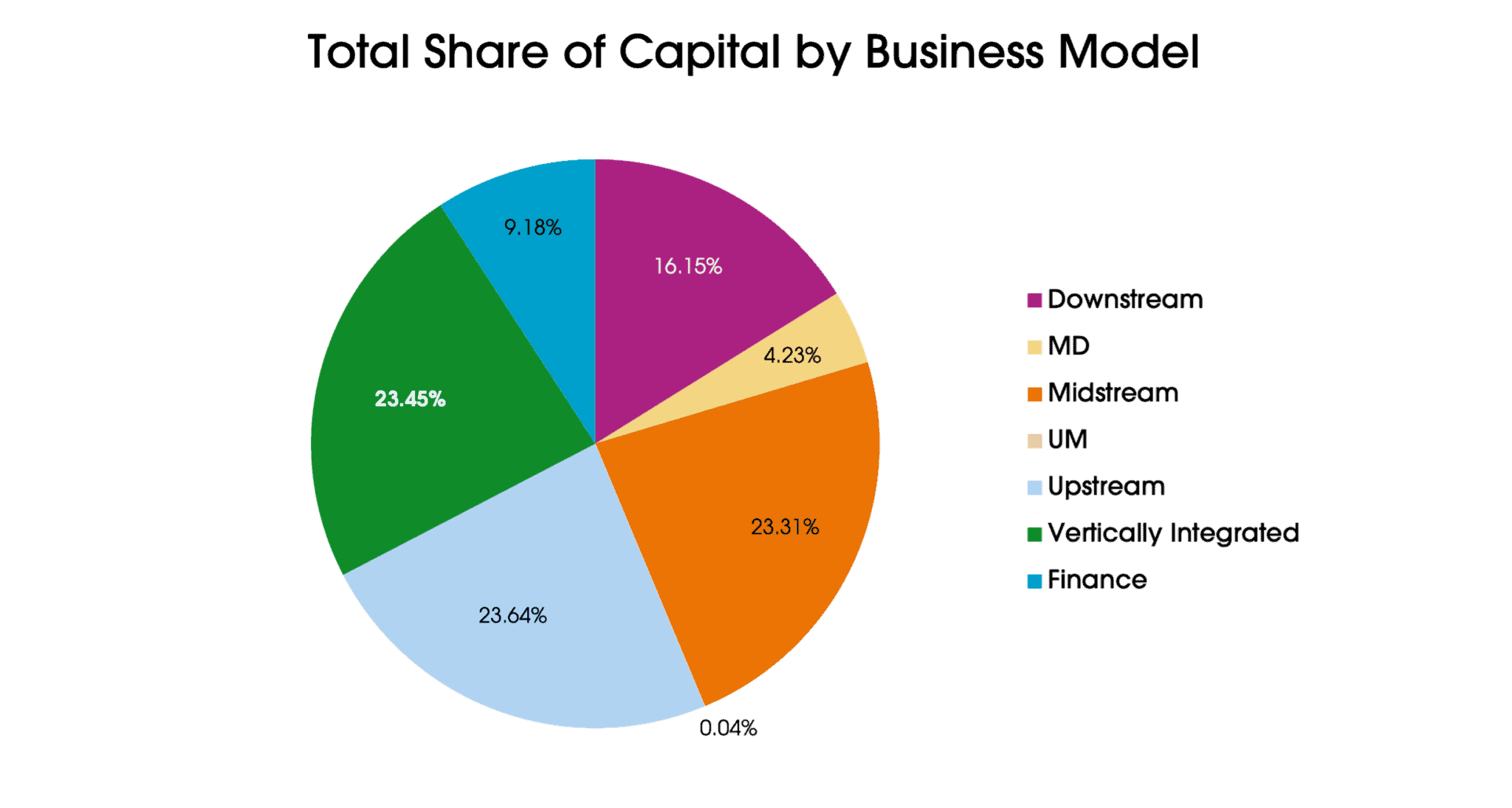

INVESTMENT INTO VERTICALLY-INTEGRATED COMPANIES IS GROWING.

Funding is pretty evenly distributed across upstream, midstream, and vertically-integrated companies. As a reminder:

- Upstream companies focus on increasing or improving production.

- Midstream companies provide logistics, processing, and wholesaling.

- Vertically-integrated companies incorporate features of upstream, midstream, and downstream models.

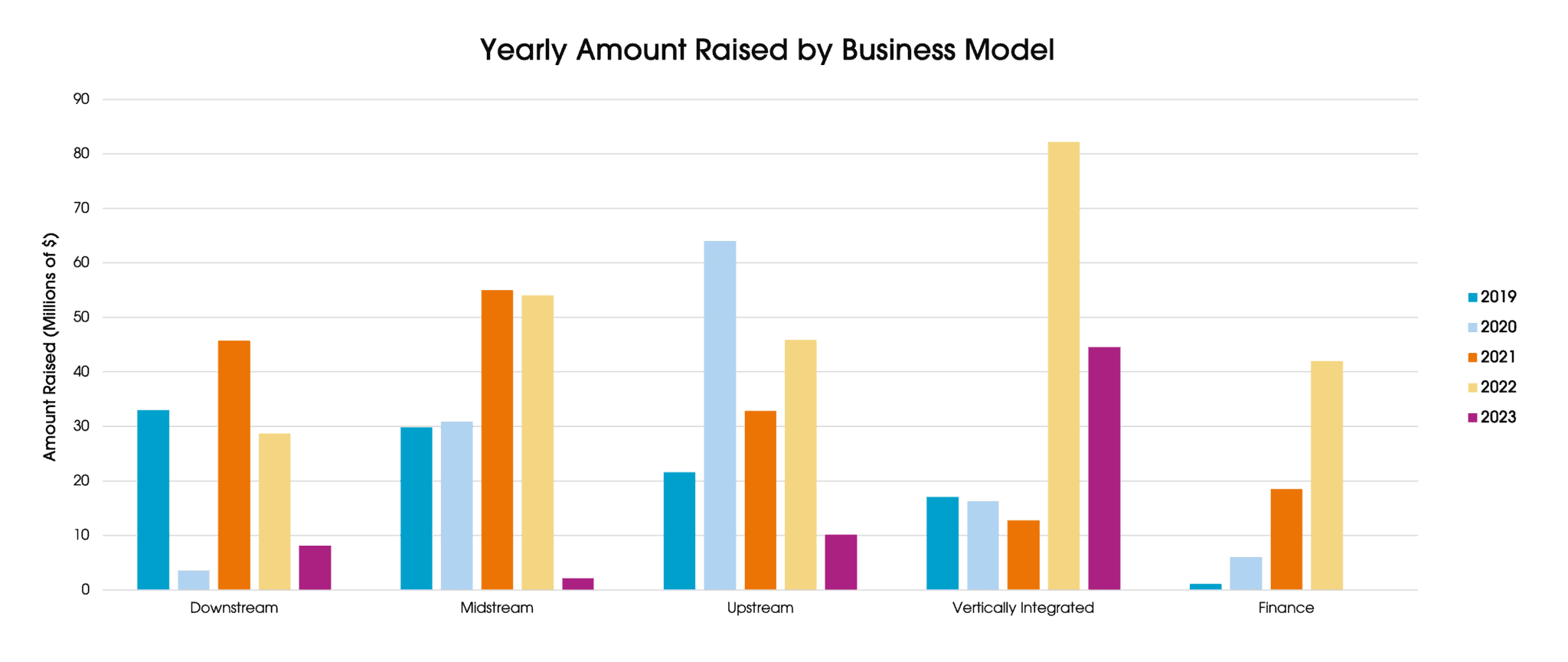

The even distribution of funding across the value chain seems to imply that most investors recognize the interdependence of operations, starting from the farm level and reaching the end customer. More interestingly, investments into vertically-integrated agribusinesses have increased, from 12.1 million in 2019 to 82.4 million in 2022.

Some of the biggest drivers of the vertically-integrated companies were Farmerline, Victory Farms, and FarmWorks, which are Acumen Resilient Agriculture Fund (ARAF) investments. While ARAF focuses on agribusinesses that enable smallholder farmers to adapt to climate change, Acumen’s broader experience in investing in African agriculture is that vertically-integrated models, especially in emerging markets, change how value is shared throughout the agricultural value chain. Investments into these agribusinesses can better help smallholder farmers increase their yields and incomes.

For example, FarmWorks is a grower, aggregator, and distributor of horticulture produce in Kenya. The company provides access to training, inputs, and land, and connects farmers to local and international markets. Through access to these goods and services, customers of vertically-integrated models, like FarmWorks, report better productivity and better incomes.

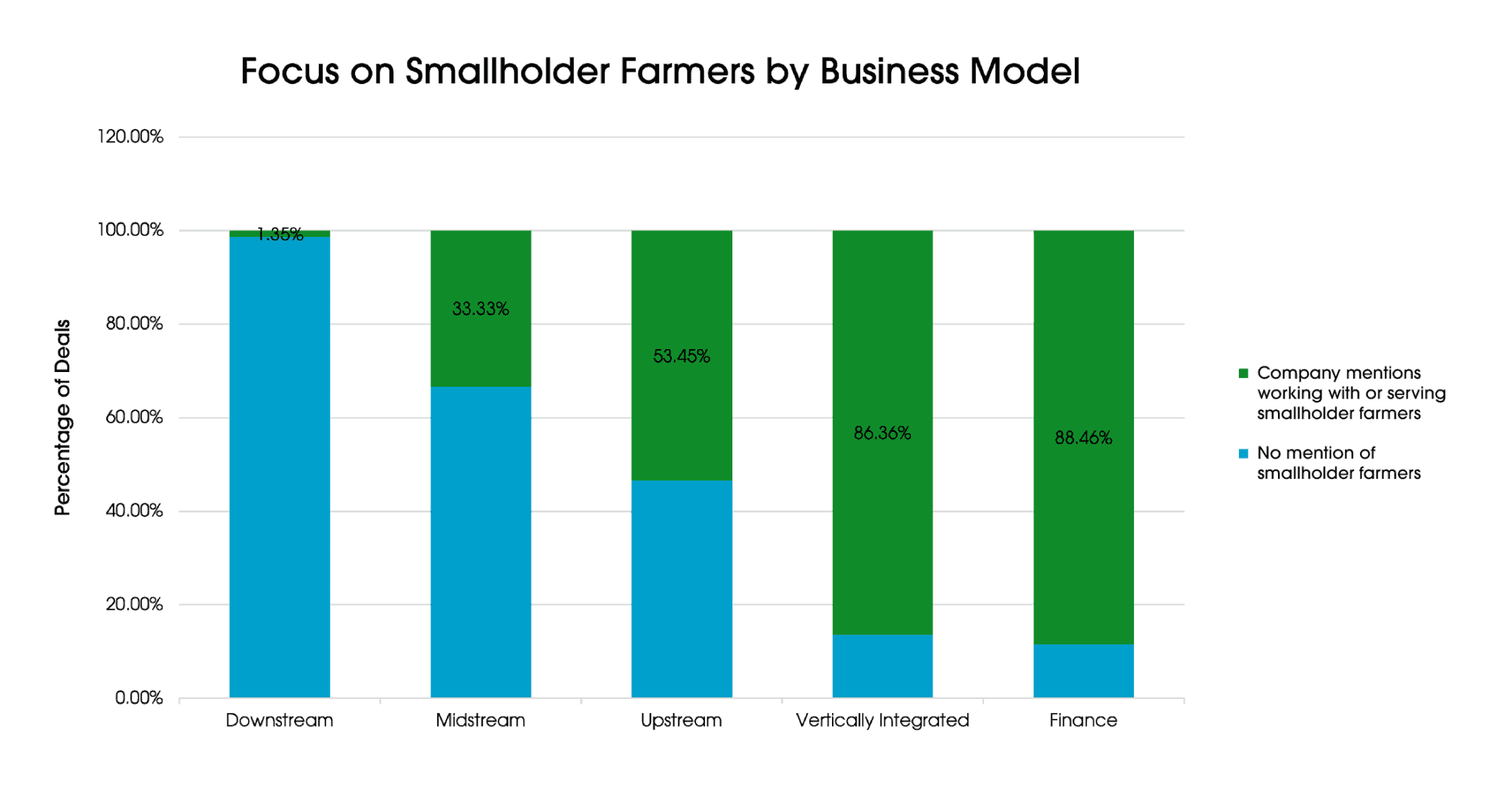

CENTERING SMALLHOLDER FARMERS IS NOT COMMON ACROSS BUSINESS MODELS.

A majority of deals (51%) and capital (54.96%) went to companies that do NOT focus on smallholder farmers. These are companies that had no mention of smallholder farmers on their company website or other public materials. However, vertically-integrated and finance companies were more likely to specifically serve or work with smallholder farmers compared to the other business models. 86% and 88% of deals into vertically-integrated and finance companies, respectively, focused on smallholder farmers, compared to 53% in upstream and 33% in midstream. This is consistent with Acumen’s experience, wherein vertically-integrated agribusinesses are often better suited to address the needs of smallholder farmers in emerging markets. While finance-based business models also indicate a focus on smallholders, Acumen has learned that a single good or service is not enough to meet all their needs. In our experience, business models that focus on upstream approaches without vertical integration (especially of market offtake) often fail to gain traction.

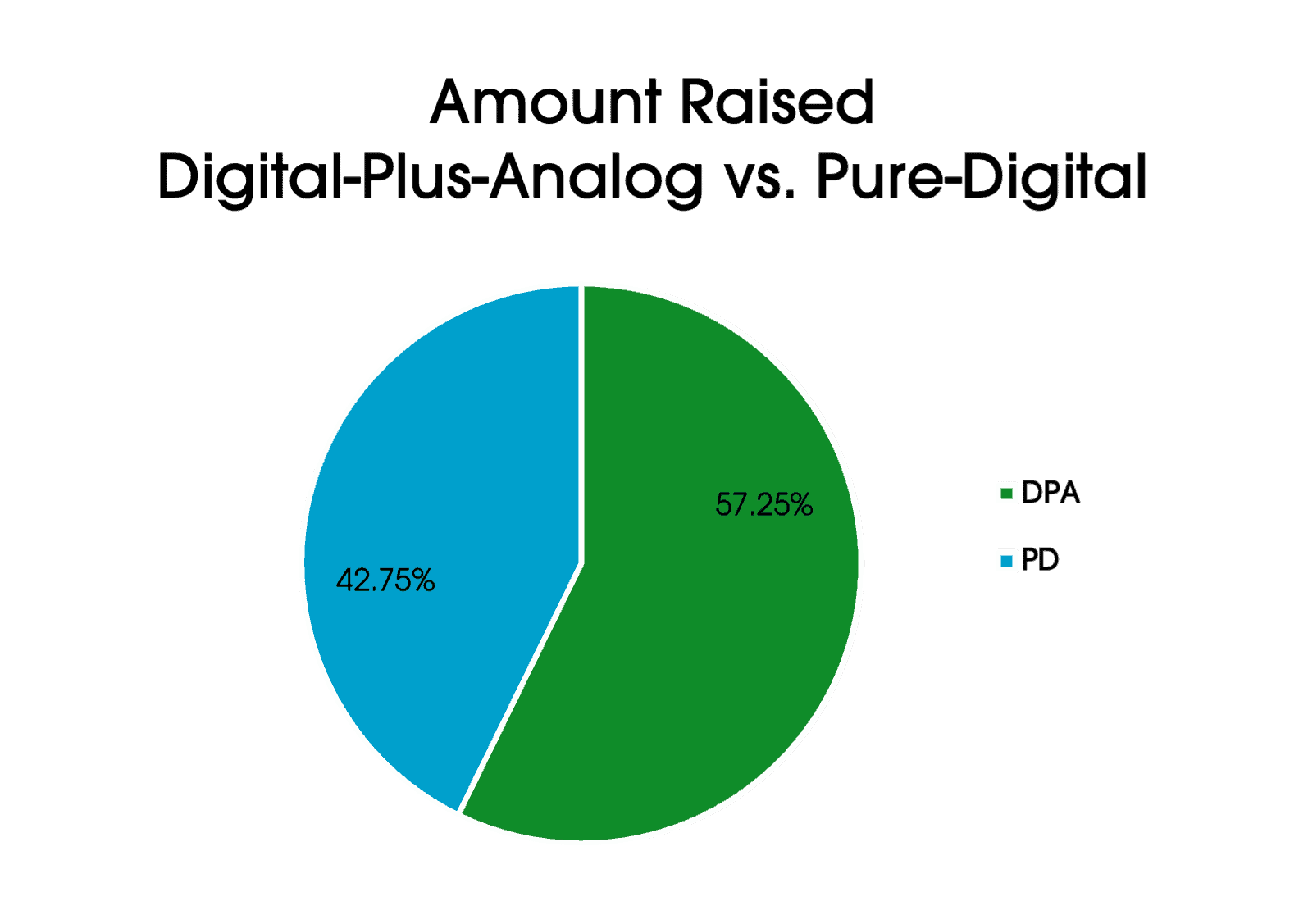

PURE-DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY CANNOT ADDRESS ALL SMALLHOLDER FARMER NEEDS.

A majority of deals went towards digital-plus-analog (DPA) solutions, which include at least one in-person touch point between the company and the customer. This includes companies that coordinate logistics and provide physical transportation for farmers’ products. Most DPA deals (55%) stated a focus on smallholder farmers, whereas most pure-digital (PD) companies did not (just 42% focused on smallholders). Tech is often touted as the solution to agriculture’s biggest challenges. While it can add value in farming, tech is not an immediate solution to improving farming productivity. Barriers include lack of digital literacy and trust, gender gaps, and high cost of services, among others.

A pure-digital application of tech without enabling a physical asset is often not enough to solve the challenges faced by smallholder farmers. They require an ecosystem of context-specific applications in order to eliminate barriers and provide holistic support. While technology can add value for smallholders, Acumen has found that smallholders need a combination of services, training, and, above all, a buyer for their product. Companies that are trying to reach smallholder farmers need to integrate digital-plus-analog solutions, whereas pure-digital companies tend to be a few degrees disconnected from immediate impact.

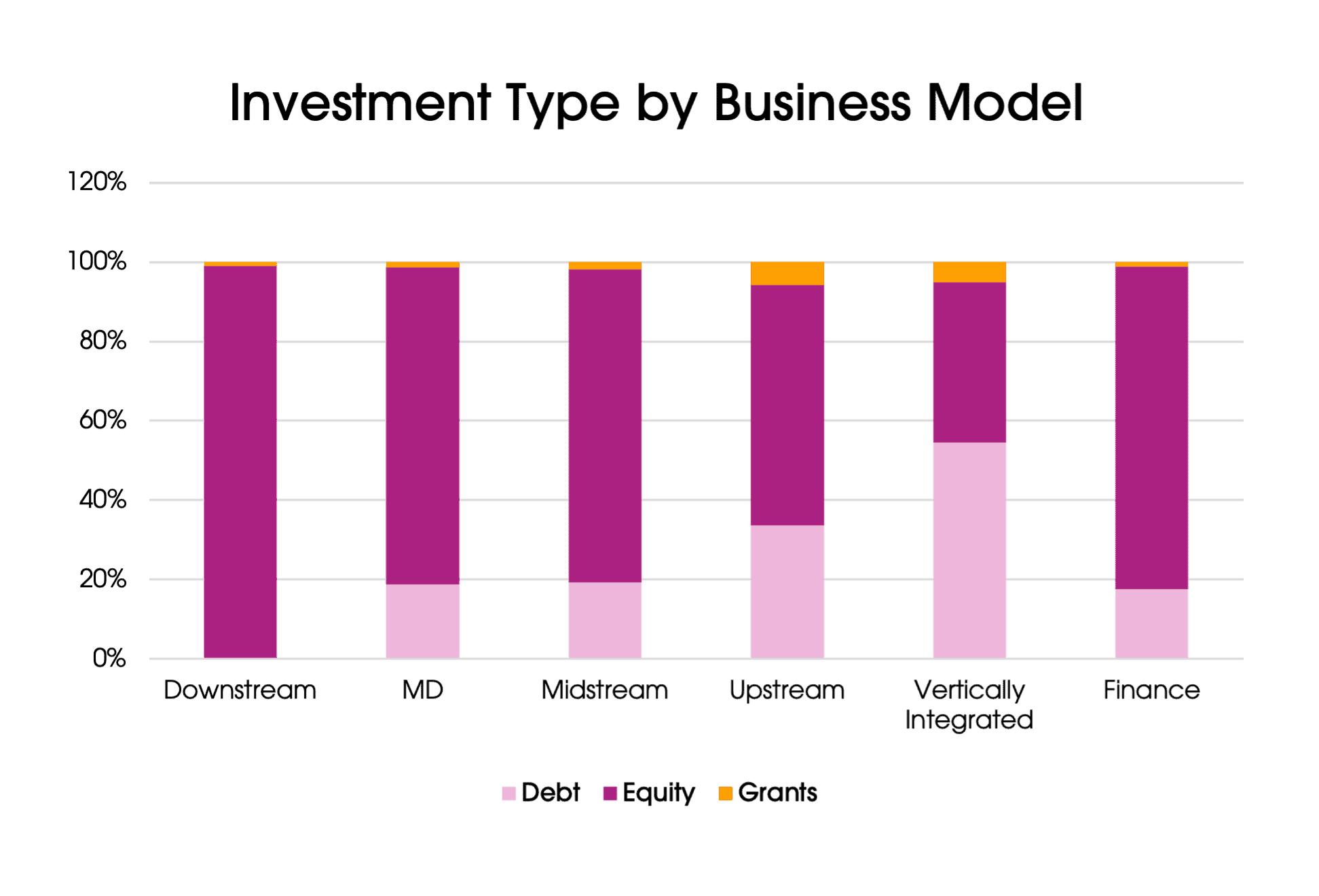

VERTICALLY-INTEGRATED BUSINESS MODELS ARE MORE LIKELY TO RECEIVE DEBT THAN EQUITY.

Business models operating in each value chain segment need a different blend of capital. Debt, equity, and philanthropy all have a role to play in the growth of an agribusiness. Philanthropic-backed Patient Capital enables companies to take the risks necessary to meaningfully impact smallholder farmers on a realistic time horizon, with reasonable return and scale expectations. The traditional VC model and its expectations were not built for the challenges and realities of African agriculture. Quick returns and scale at all costs will not solve the urgent needs of smallholder agriculture.

AFRICAN AGRICULTURE REQUIRES MORE CAPITAL AND MORE APPROPRIATE CAPITAL

Though inherently risky, investing in African agriculture is not just worth the gamble; it is absolutely critical. One-quarter of the world’s population makes a living through smallholder agriculture, which produces one-third of our global food supply. Smallholder agriculture needs much more capital and much more appropriate capital driven to many more companies. Boosting agricultural investment is the low-hanging fruit that can transform food systems, strengthen climate resilience, and improve millions of lives.

This article was originally published by Acumen.